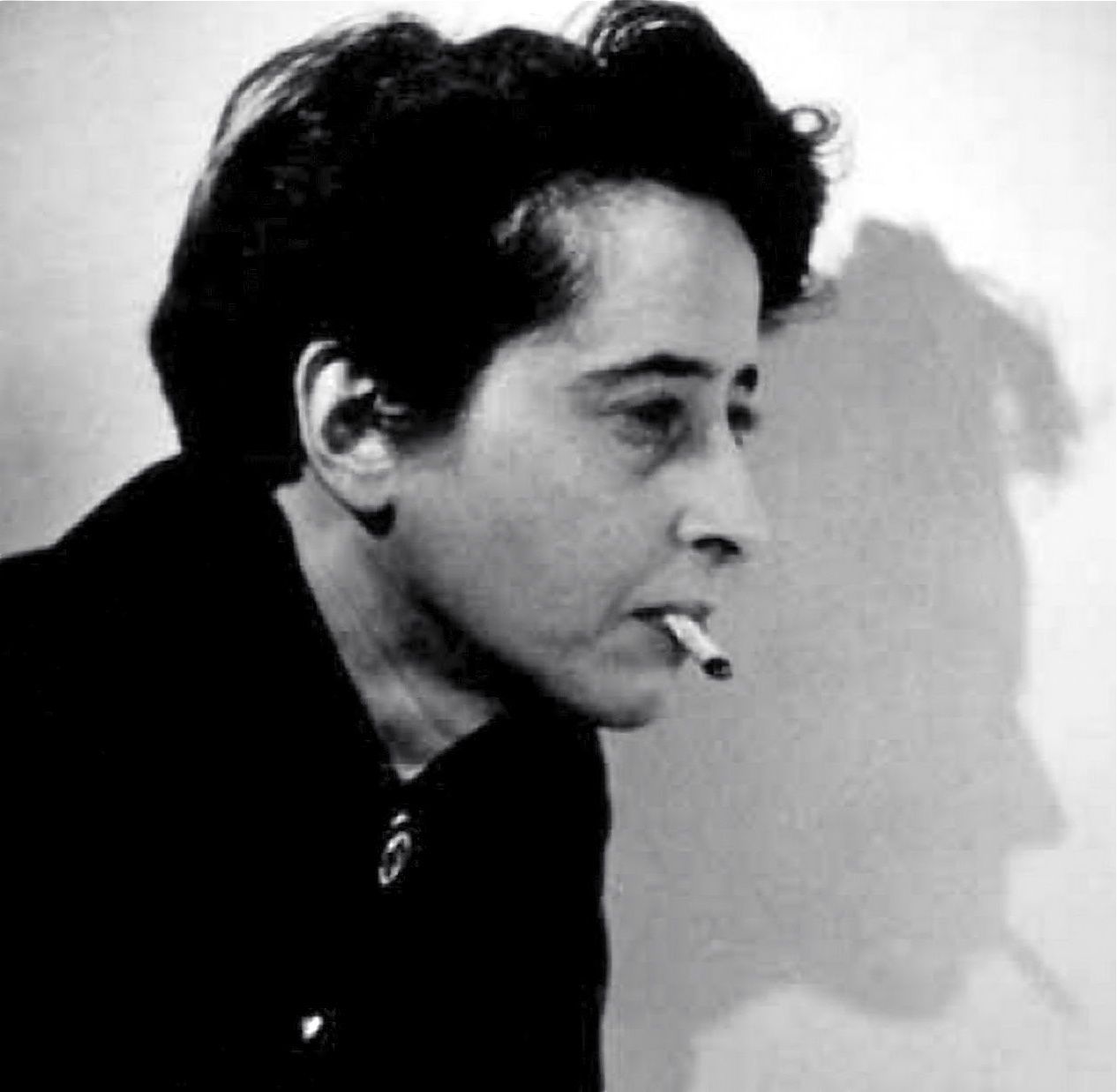

Arendt, according to Robin, spent parts of her career, including Eichmann, developing and elaborating upon the classical instinct that intentions, whatever their meaning, can never be determinative of moral innocence or culpability. Rather, actions are the only salient data when it comes to judging good and evil.

This subject was a primary question as well in something I read yesterday, a bizarre and bewildering email exchange between Noam Chomsky and the writer Sam Harris. (Also very long. If you have the time to read all this, that's great, I think you'll be the better for it, but, as I frequently admonish myself: shouldn't you be working?)

Chomsky (whose indefensible belligerence throughout the exchange often renders his exact position undiscoverable) seems ultimately to hew to Arendt's view. Muddied as his logic is by the imprecision of his own pique, Chomsky clearly rejects (or at least considers somehow irrelevant) Harris's position that the 9/11 hijackers' intention to kill as many innocent people as possible provides a meaningful way of distinguishing between the moral status of their act and the moral status of (the example Chomsky and Harris discuss) Bill Clinton's 1998 decision to bomb a chemical/pharmaceutical laboratory in Sudan, which Chomsky claims resulted in perhaps tens of thousands of Sudanese deaths. (Note: as best I can tell, this is in dispute.) Chomsky points out (over and over) that intentions, at least declared intentions, have been offered as either justification or exculpation for the most grievous crimes of history, Hitler's included. They are, therefore, no guide to the morality or immorality of acts or actors.

My question is why so much energy is being spent resisting the felt reality that moral responsibility, both in itself, and as we are capable of judging it, is a composite of act and intention? Every day, when faced with uncertainty regarding the moral status of actions (drone strikes, police tactics, votes in favor of free trade), we take into account both intentions and actions, we go through that complicated but familiar moral process of weighing and comparing, of judging the extent to which any given actor seems culpable. Different cases warrant differing degrees of import assigned to the brute facts of the event and the intentions of the actors involved. And this is fine. We know how to do this. We are capable of looking at a given case -- say Clinton's -- and determining that the relevant actor, whatever the outcome of his action, seemed to be doing his best; we are capable of looking next at a different case -- say Eichmann's -- and concluding that the sheer scale of horrific facts overwhelms any recourse to exculpatory motives. In human lives, both elements are real, the mitigation of benevolent intent, and the conclusiveness of inescapable data. To deny either of them is to deny us the fullness of our judgements about life and meaning. We know how to do this.

Or do we? Saul Bellow (of whose work I'm a great admirer -- see my rapturous post about discovering Augie March here) used to say that a distinguishing characteristic of modernity is that it calls upon us to make judgements almost constantly "about genocide...or about famine, or the blowing up of passenger planes" -- this is from a 1990 lecture Bellow gave at Oxford -- "and we are all aware that we are incapable of reacting appropriately." Elsewhere, Bellow adds to the list of those imponderables which we still somehow sense we must form the right opinion about: "The new Russia and... China, and drugs in the South Bronx, and racial strife in Los Angeles...the disgrace of the so-called educational system...ignorance, fanaticism...the clownish tactics of candidates for the presidency." Bellow wrote that in 1992. But it seems prescient now -- interested in 'liking' Hilary Clinton or Jeb Bush on Facebook; care to re-tweet a Foreign Affairs article written by a Putin apologist?

Bellow's point was that we can't do it anymore, we don't, after all, know how to judge all this moral flotsam. In Bellow's view, shaped as it was by the social dissolutions of the second half of the 20th Century, the result of our inundation was a violent lashing out, drug use, crime, sexual profligacy, etc.

Leaving some of Bellow's legendary crankiness aside, and whether he was right or wrong about the causal relationship between demands on our evaluative faculties and the social upheavals of the post-war era -- and those upheavals themselves having become phenomena on which we're called to render judgement -- I wonder if we might not arrive at an understanding of our present age as what I've called it in the title of this post: The Age of Moral Exhaustion.

Using the Bellovian model where there was at least a correlation (causation? Eh, maybe not...) between our heightened awareness of the universe of morally ambiguous facts, and the shattering instability of the 1960s and 70s, would we be entirely crazy to posit a current state of affairs in which Americans have simply given up moral parsing? Is skyrocketing income inequality the result of surrender? Do Arendt's and Chomsky's arguments against the moral relevance of something so messy and ineffable as intent represent a kind of desperation for starker, clearer means of determining moral responsibility? Is America retreating into the tribal bitterness of partisan politics because it's just easier to pick a side than it is to evaluate every policy argument de novo?

Well, there's a lot of tangled (and perhaps some facile) thinking in the preceding paragraph, I admit. But this is a blog post, not a dissertation or a legal brief. Analysts could pick apart individual causal propositions, and they're welcome to do so. What I'm aiming at, though (and maybe this is the only thing a blog post can do...if it can even do this) is not analytical accuracy, but an emotional insight, a definitive vision of who we are now. I'm trying to name an epoch. (Because, you know, why not? What else have I got going on, right?)

The Age of Exhaustion. Moral exhaustion. Should we be arming the moderate Syrian opposition? Can Iran ever be a partner in nuclear non-proliferation? Is it wrong to buy vegetables that have to be shipped all the way from another hemisphere? Shouldn't Europe be allocating more funds to assist in the rescue of refugees at peril in the Mediterranean? We used to know how to make exceedingly subtle judgements about people and their decisions. And maybe we still do, somewhere in our beat-to-hell spirits. But, Lord, we're tired now, civilizationally tired. And we don't want to do it anymore. Am I wrong?

No comments:

Post a Comment